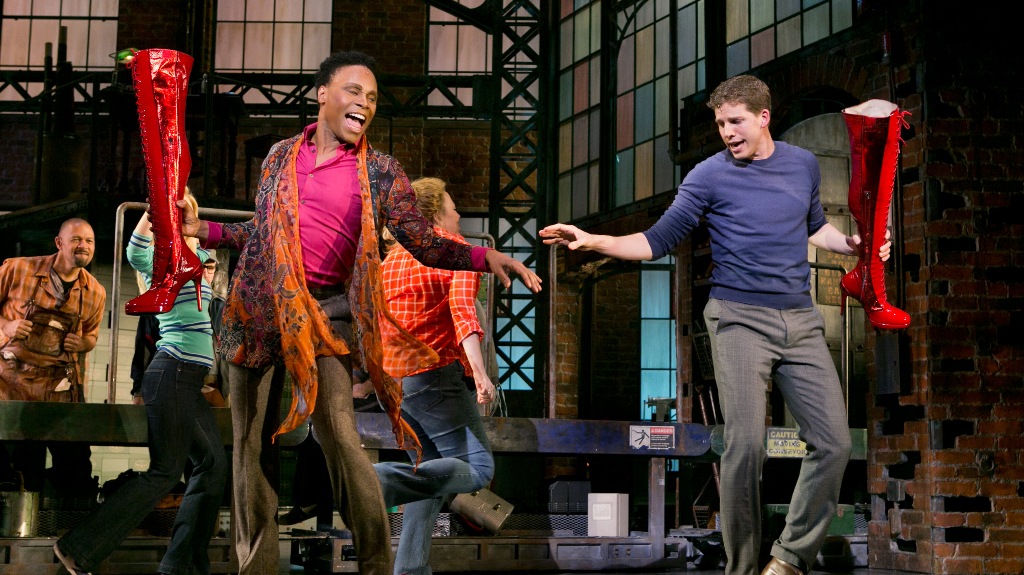

KINKY BOOTS

Book by Harvey Fierstein

Music and Lyrics by Cyndi Lauper

Based on a screenplay by Geoff Deane and Tim Firth

Starring Callum Francis and Christian Douglas

Directed and Choreographed by Jerry Mitchell

Stage 42

Official Website

Reviewed by David Spencer

For all that Kinky Boots has returned as triumphantly as it left, seeming to be a hit musical all over again—and in even better shape, cleverly trimmed, even more fleetly delivered than before—I just don’t have that much to say about it, and I don’t mean that to sound ungenerous of spirit. In many ways I admire it. But there are four huge truths that still obtain.

(1) Story-wise it follows a very familiar trajectory. A shoe manufacturer (Ryan Halsaver) hopes his son (Christian Douglas) will take over the business but his son has other ideas. When his father dies (offstage) and he receives the news in the very next scene, he is pulled back into the business anyway, a classic reluctant hero. He has to save the business for the sake of the workers, most of whom are people with whom he has grown up. But he needs a new angle, a new product line—which he finds via meeting an unlikely partner, an extravagant nightclub drag queen (Callum Francis) , who tweaks him to an inspiration: women’s boots strong enough to support the weight and the stride of men. There are forces that need to be won over, there’s the start-of-story upwardly mobile fiancé (Briana Stoute) vs. the right girlfriend in the shoe factory (Danielle Hope) if he would only see. There’s the workplace tough who thinks he knows what being a man is all about (Sean Steele) until the drag queen teaches him a thing or two. And ultimately there’s our hero becoming so obsessed with the that he loses sight of who his friends are…until, left alone to ponder his short-sightedness, he gains moral redemption, whereupon surprise-surprise, his loyal friends have returned. I know this sounds like a truckload of spoilers but I promise-promise-promise you, there’s not a plot point you won’t anticipate, whether you’re into it or not. Everything in Kinky Boots is, like the long red footwear of the title, about delivery of the product line, the new look on an old item. It’s about how it gives you what it promises, and how much what it promises is what you want. Because there’s no question it’s what you’re going to get.

(2) As a piece of writing, it’s both expert and middling. Librettist Harvey Fierstein (adapting the 2005 screenplay by Geoff Deane and Tim Firth) delivers the archetype characters boldly, gives them entertaining lines to say, and backloads his humanist accept-people-for-who-they-are riff (familiar from previous shows of his) into the bargain. Composer-lyricist Cindi Lauper follows the route of every single pop writer/recording artist who has ever decided to moonlight in theatre (with the exception of David Yazbeck, who was weaned on musicals and dramatic writing) in that her songwriting is pop-generic, its only specificity a certain energy/genre appropriate to the moment. She’s unable to deliver fleshed-out character as opposed to character-type template; she’s largely unable to move story forward or deliver revelation in song, mostly vamping on stuff we already know (I say mostly because there are a few “false positive” indicators in the first ten-or-fifteen minutes that might give a first-time viewer the mad hope that she may be the one to come to the gig with a miraculous, raw instinct her predecessors have lacked); her song structures can be dramatically unwieldy; annnnd let’s not even get into proper rhyme and accent. Pop writer. Not her thing. But…I have to add, the newly streamlined libretto helps enormously. I’m relying only on memory, so I’m prepared to be chagrined if I’m wrong, but it seems as if we’re not sitting with as much repetition, that the creative team has, here and there, targeted where the lead-in to a song and the song itself were doing similar work, and are now letting the songs carry all they can.

(3) The audience doesn’t give a flying fig that what’s on the page is less art than artful efficiency. Director-choreographer Jerry Mitchell understands how thoroughly this material is about hitting certain marks, meeting certain expectations, pushing certain buttons and delivering on promise—and mostly at a speed that discourages thinking about things too deeply. One could argue that such is the secret of any musical, but I think you know what I mean in an environment that is not about exploring the form, but exploiting it to deliver sentimentality and show business flair in a package that satisfies the current benchmarks of populism (and its currency is very important to its impact). I almost said undiscerning populism, but that would be unfair and inaccurate. Even a populist audience knows when pabulum is delivered without sincerity or style. No, Mr. Mitchell believes in what he delivers; and what he delivers—and I mean this as high praise—is pabulum for the connoisseur. And his very discerning audience is suitably pumped. From the very opening bit—a clever riff on the “turn off your cell phones” caution—getting a meticulously orchestrated rush for your money’s worth is never in doubt.

(4) That you’ll share the rush is also never in doubt. The energy and conviction of the evening, the charismatic fire of the cast, is too persuasive. But how you’ll feel about it is another matter. If you’re like most of the audience, you’ll have an exhilarating time and be well-pleased. If you expect to see a show that enriched the repertoire by reaching for something rare and special…perhaps not so much.

When the show first opened, a fellow musical dramatist said to me of Kinky Boots, “I finally despair that the American musical is getting away from us”—by which he meant turning its back on its best and noblest standards of craft and aspiration in favor of a quick MTV fix. For various reasons I wasn’t prepared to agree with that then…and now it’s become a more complicated issue…but the success of Kinky Boots (and I don’t begrudge it; it still comes honestly) represents, and perhaps even crystallized, a subgenre I think of as “the package musical.” It has been attempted before and failed spectacularly (Lestat comes to mind) but that was due to bad casting of the creative teams. You can’t just slap a brand-name into the by-line spot and expect rewards.

But Harvey Fierstein and Cindi Lauper have exactly the right sensibility for these characters and their story, indeed an almost autobiographical sensibility. And Jerry Mitchell knows how to frame it spectacularly. And your degree of enjoyment will depend upon whether you find it to be art…or merely artful…(and perhaps I had more to say about it than I thought…)