A WONDERFUL WORLD:

The Louis Armstrong Musical

Book by Aurin Squire

Conceived by Andrew Delaplaine and Christopher Renshaw

Directed by Christopher Renshaw

Featuring James Monroe Igleheart

Directed by Christopher Renshaw

Studio 54

Official Website

Reviewed by David Spencer

Well, how wonderful a world is it really?

With regard to the fecund and profitable subgenre of jukebox bio, celebrating the life of one or another popular music icon, there seem to be almost inevitable tropes:

The ones about women usually chronicle how, in pursuit of their careers, they made their way in a world dominated by men by heeding the guidance of the strong, wise women who came before, and were/are able to teach by example and anecdote. (To give Hell’s Kitchen its due, it’s Alicia Keys’ “origin myth” rather than her career-life overview, so the distribution/execution of variant elements is fresh enough to count it an exception.)

The ones about men tend to chronicle how, in pursuit of their careers, they messed up their long term relationships with long-suffering women and finally (perhaps) conquered or at least tamed the demons within that caused them to be such self-indulgent putzes. (The hit play, Stereophonic, has its share of this too.)

On the one hand, the dramatic work about a driven male artist that doesn’t chronicle his busted relationships is rare. (Heck, what’s The Agony and the Ecstasy about if not Michelangelo pissing off the Pope for taking so long to paint the Sistine Chapel? “When will you make an end of it?” “When it is finished.” But I digress …)

However, what’s very different about A Wonderful World: The Louis Armstrong Musical is its giddy nonchalance about Louis Armstrong’s pathway through femininity—make that feminine companionship. As his adventures and misadventures take him from New Orleans in 1910 to Chicago in the 1920s, Hollywood in the 1940s and New York after, and on into the 1970s—going from itinerant jazz sideman to headliner to movie star to cultural icon—he sure has fun moving from babe to babe, like it’s his entitlement. (I couldn’t help but think of a Jules Feiffer novel title: Harry, the Rat with Women.) And it’s not as if he isn’t called on it now and again, or as if the women themselves are without their personal michegossen (let’s call it a jazz term), but in Aurin Squire’s libretto, there’s nonetheless a not-entirely-tacit subtext of, Oh, well, what’cha gonna do, he plays jazz trumpet. Unlike, say, the recent portrayal of Neil Diamond (with that jukebox tuner’s coincidentally synchronous title, A Beautiful Noise), our Louis is never very angst-y. How does this show get away with that in 2024?

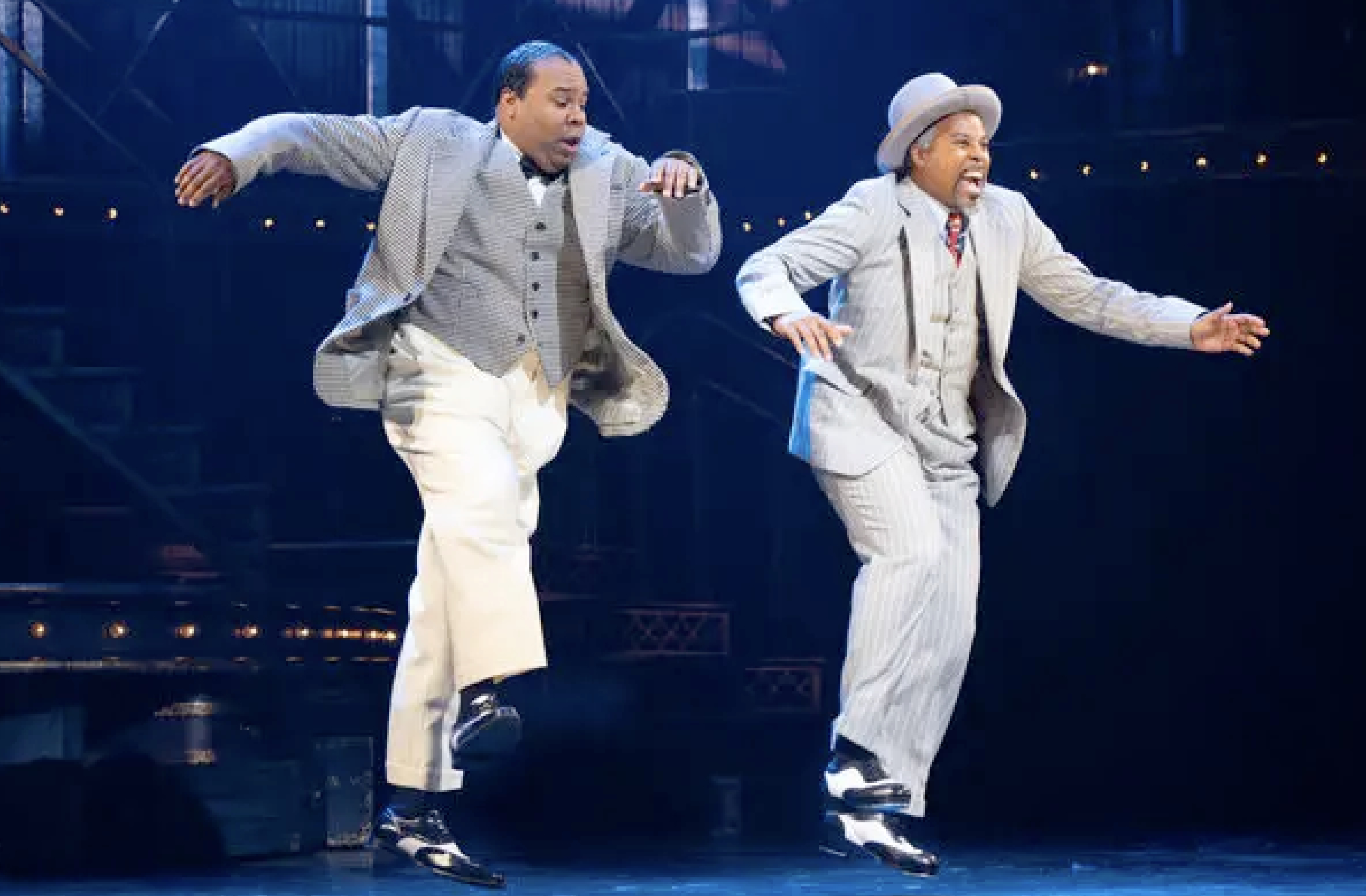

Well, in part, I suppose, because what’s presented is likely the way it happened, more or less. The subject is, after all, Louis Armstrong and no one wants to see (or create) a Louis Armstrong bio-musical in which he doesn’t live up to his popular persona. (There’s even a segment during the Hollywood sequence—containing arguably the show’s best number—in which Armstrong and Lincoln Perry [more famous as Stepin Fetchit] celebrate each having codified the salable schtick that defines their public image and has secured their stardom.) And in part, it’s because the jukebox of Armstrong’s life is filled with mostly positive songs. It’s a fool’s challenge to fashion a musical bio driven by psychological investigation when the songs you have to draw from are the likes of “It Don’t Mean a Thing (if you ain’t got that swing)”, “You Rascal You”, “Cheek to Cheek”, “Hello [freaking] Dolly”, fer goshsakes, as well as that title song; his signature song. Which is, you know…the show’s title!

And in furtherance of that point, one must pause to acknowledge the sprightly direction of Christopher Renshaw—co direction by Christina Sajous and James Monroe Iglehart—the sprightly choreography of Rickey Tripp, a musical team of class-A jazz specialists including Branford Marsalis (arrangements and orchestrations) and Daryl Waters (vocal arrangements and incidental music)—many, many others including the tech and design personnel…and of course, the cast, especially the aforementioned Mr Iglehart who captures the essence of Armstrong, Dewitt Fleming Jr, brilliantly balancing the Lincoln/Fetchit dichotomy (an onscreen layabout who offscreen is savvier than the white audiences buying into the slow-shuffle that made him a fortune); and the the women of the saga: bold, delightful contrasts personified by by Kim Exum, Darlesia Cearcy and Dionne Figgins.

But back to our thesis: On the one hand, in this day and age where the insistence of emotional accountability has insinuated its tendrils into popular culture with random abandon, story-character-and-period-appropriateness be damned, there’s something refreshing about this throwback way of treating Louis’ womanizing as a robust impulse he’s helpless to manage. On the other hand, the avoidance of moralizing and other such bog-downery keeps the show running like a jukebox. It’s not that you forgive Armstrong so much as that he doesn’t ever disappoint you by failing an imposed standard. The dancing, the singing, the entertainment value of sheer showmanship are sufficiently enticing to keep you happily on the ride.

But “on the ride,” in this case—as the above might suggest—doesn’t mean emotionally engaged. But maybe you don’t have to be; the sense of catharsis comes with its infectious energy delivering payoff after payoff. A Wonderful World is basically a revue with a biographical thread running through it—and as such is the best variety show the town has seen for ages.