McNEAL

by Ayed Akhtar

Directed by Bartlet Sher

A Production of Lincoln Center Theater

at the Vivian Beaumont

Starring Robert Downey, Jr.

Reviewed by David Spencer

For all its being a high-tech-fueled tragi-comic diving into the controversies of Artificial Intelligence, and its impact on culture, art, society and relationships, McNeal, at its core, very familiar: Portrait of a dissolute charismatic professional—in this case a celebrated novelist—whose success exists alongside his self-destructiveness, which includes alcohol abuse (inflicted upon himself) and mental abuse (inflicted upon family and others) and not much evidence that he’s got any wiring to enable redemption. He’s already tipping off the ledge into spiral-down mode when we meet him. A classic paradigm.

The saving grace of characters like this tends to be that they’re iconoclastic and funny; and Robert Downey, Jr., inhabiting McNeil, handles that, and the sometimes subtle/sometimes brutal narcissism easily. But the play itself isn’t as well-centered.

The issue, of course, surrounds the legitimacy of his career. Did he steal material from the deceased wife who was once devoted to him or simply refashion it from a raw state, as he tells his potentially vengeful twentysomething son (Rafi Gavron)? Did he crassly exploit the intimate events of a former lover’s (Melora Hardin) most difficult period; or was he exercising the prerogative of writing about things he knows and observes? And with the advent of AI technology…if he asks an ultra-sophisticated program to fashion a contemporary story of a certain type, drawn from elements of various classics but filtered through his own prose style, and the book is among the successes that wins him a Nobel Prize for literature…is he a charlatan or a modern practitioner, using available tools toward a new, inevitable kind of creation? Of course, his publishers don’t know; nor even his tireless agent (Andrea Martin).

And the ultimate problem is that the play itself seems itself like a ragout fashioned out of its predecessors in the genre. No mistake, Mr. Akhbar is possessed of elegant wordsmithery, the ability to create rounded characters and an attunement to narrative energy…but these are only variations of confrontation-configurations we’ve seen played out before, on stage and screen—and page, having an even longer tradition in literature.

What would have made McNeal unique of its type? It’s impossible to be categorical, but one possibility might be a core trait unique to the main character, setting him apart from the category. Take the implicit title character in the brilliant Australian TV series, Rake. Cleaver Greene (as personified by its co-creator, Richard Roxburgh) is a brilliant courtroom barrister whose personal life is a shambles. He too has a dissolute lifestyle and has alienated people he loves…but most of them remain somehow in his orbit, because he does love them; and his saving grace is that he will throw himself even further under the bus to protect them. That massive contradiction is what keeps us on his ride, rooting for him in spite of his excesses.

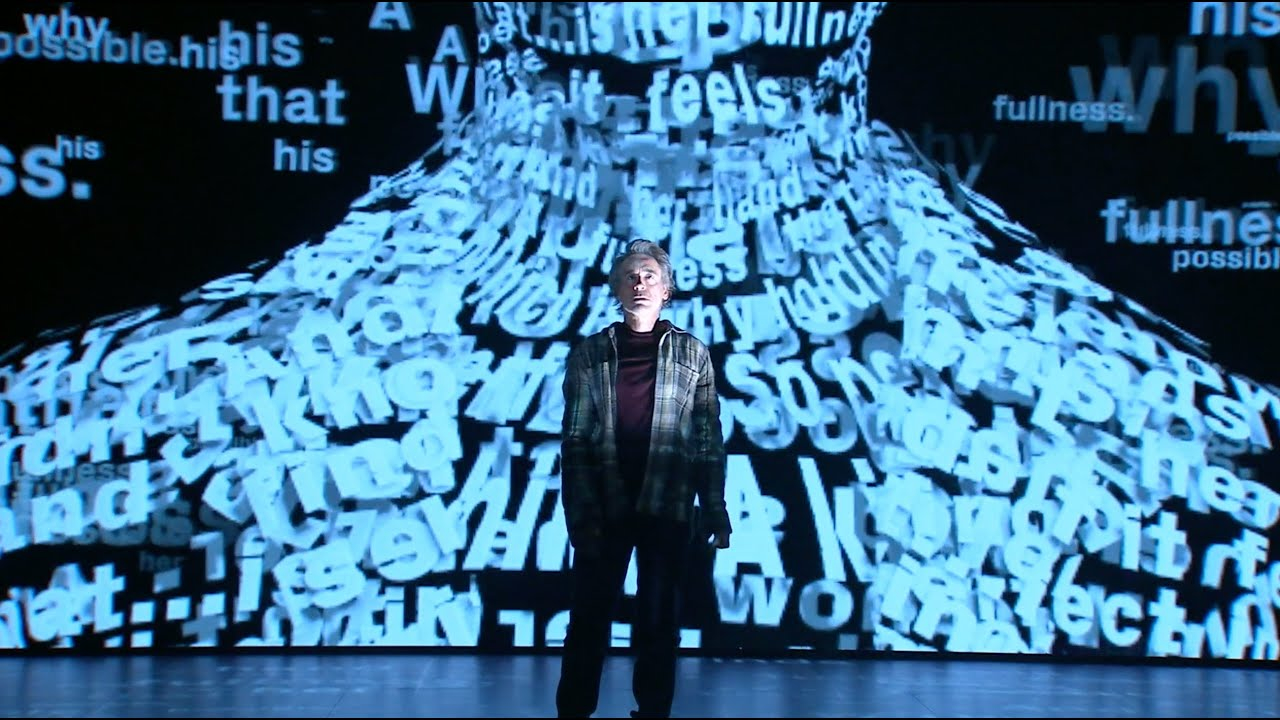

But even with similarly interesting satellite characters played by a cast up to Downey’s level of excellence—and despite Bartlett Sher’s as always impressive direction—this time fueled by impressive high-tech effects—McNeal’s ride is far less fun than Cleaver’s, harboring the inverse contradiction: Because since the play begins with MacNeil already dissolute, already having used people up, he’s already morally compromised. And likewise already committed to his path. He has nowhere to go. He can only keep running to stay in place until his own biological tech hits obsolescence.

I’m not saying McNeal should have started out as a cipher or an innocent; by all means introduce him as a glib, alcoholic narcissist; that makes him engagingly dangerous. But as dramatized, the plot denies him the more potent volatility that would come from his having something truly NEW at stake. From facing, say, that he has nothing in real life left to steal. Shouldn’t we see him take that first step into “creativity” via electronic surrogate—as a calculated choice rather than a mid-point reveal? Nor am I saying the choice must perforce be wrong. By all means, leave that judgment to the audience. Because then the consequences—and they ultimately must be derived from the act—as are controversial as the choice itself.

But with McNeal’s use of AI dramatized as reveal, what’s ambiguously presented here can only be the possible weight of self-loathing he may carry, knowing that he didn’t achieve his acclaim without electronic help; knowing further that the grand high oohbahs who confer literary greatness were utterly fooled. (But this is never articulated. It’s implicit as something you think about later, but never a seed pointedly planted in the moment.)

One can argue, with cause, that what I propose is the equivalent of dramatizing backstory. But in this case I’d say treatment is the determining factor. If McNeal has nothing to struggle with other than to see if he can continue to manipulate his way out of personal relationship accountability, the controversy of AI is not the point. It’s the McGuffin. And that’s why the play—though written with skill and verbal wit—is such a throwback.